http://finance.yahoo.com/news/cockpit-japans-kamikaze-pilots-150001463.html

------------------------------------------------------

By Maiko Takahashi 23 hours ago

(Bloomberg) -- Hisashi Tezuka knew his life had been spared when he heard the Emperor’s voice crackling through the wireless.

As Hirohito

announced Japan’s wartime surrender on Aug. 15, 1945, the young kamikaze

pilot was on a train to the island of Shikoku to carry out his

sacrificial mission. He received his orders just two days earlier at a

base about 1,150 kilometers (715 miles) to the north.

“If

we’d been taken by plane, we’d have arrived before the war ended,”

Tezuka, now 93 and one of the few surviving kamikaze, said in an

interview at his home in Yokohama. “It was like fate intervened.”

Tezuka

was one of a few thousand men, some as young as 17, in Japan’s

so-called special attack unit, or tokkotai. Another was Tadamasa Iwai, a

94-year-old who trained to be a human torpedo and suicide diver. Both

had late reprieves, both saw the futility of the war, and both became

passionate pacifists.

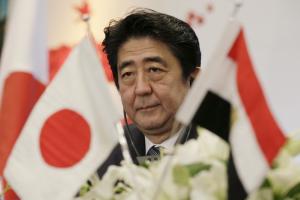

This

is a year of painful remembrance for Japan as the country marks the 70th

anniversary of its surrender in World War II, a conflict that killed

more than 30 million people in Asia and left the nation in ruins. Prime

Minister Shinzo Abe has hinted he’ll omit descriptions of wartime

aggression in a statement for the anniversary, risking anger from

countries like China and South Korea that felt the brunt of Japanese

belligerence.

Abe

is also seeking to loosen the restraints of the war-renouncing

constitution imposed by the U.S. and strengthen Japan’s role in global

security. Even so, polls show the Japanese public is deeply ambivalent

about adopting a more muscular foreign policy.

Fifty

percent of respondents to a survey published in the Nikkei newspaper on

Feb. 23 said they opposed legislation that would allow Japan’s military

to defend allies, while 31 percent supported the bills that are set to

be submitted to parliament in the next few months.

“I’m

concerned that Japanese politics and attitudes have shifted to the

right recently,” said Tezuka, whose wrinkles and stuttering walk betray

his years. “When Abe says he doesn’t want to dwell on the past, it’s

like he is returning to the prewar regime.”

As

China asserts its territorial claims in the East China Sea, Abe has

increased defense spending to a record, eased restrictions on weapons

exports and is seeking a constitutional workaround to be able to project

force abroad. His efforts are favored by the U.S., which is treaty

bound to defend Japan in the event of conflict, and have been denounced

by China and South Korea.

Even

though Iwai joked often during an interview at his small Tokyo

apartment, he became furious when talking about Japan’s current

political climate, for which he blamed the education system.

“They don’t

teach what really happened at schools,” he said. “Textbooks call it an

’advance’ rather than an ‘occupation’” by Japan.

By

the summer of 1944, Japan’s weakened air force had become unable to

match the U.S., prompting commanders to develop the suicide strategy.

From October that year through to the final days of the war, Japan flew

2,550 kamikaze missions with a successful hit rate of 18.6 percent,

according to the U.S. Strategy Bombing Survey on the Pacific War. They

sank about 45 vessels, mostly destroyers, and damaged dozens more

including aircraft carriers and battleships.

Three Choices Both men described the moment they knew their fate was in the hands of their commanders.

One day in training, Tezuka was handed a questionnaire with three choices: “I strongly want to be a kamikaze”; “I want to be a kamikaze”; and “I don’t want to be a kamikaze.” The final one was not an option, he said.

Iwai and his peers were summoned to a training ground at their base, where an officer asked them if they wanted to pilot the manned torpedoes -- again an offer they couldn’t refuse.

While

both Iwai and Tezuka were opposed to the war, they were committed to

their assignments. They look back with a mixture of guilt, relief and

anger.

Tezuka said that many men, including a friend, died during training flights that involved soaring to 3,000 meters before nose-diving to a practice target.

“I was sorry for his death -- not just because he died, but because he couldn’t die as a kamikaze,” he said. “Everyone was serious about the training. We didn’t want to die meaninglessly before we departed. We really wanted to succeed as kamikaze.”

The stories of these pilots have returned to prominence in popular culture in recent years.

“Eternal

Zero,” a 2006 novel by Naoki Hyakuta about a young man’s search for the

truth about his kamikaze grandfather, was a best-seller. Abe, a friend

of the author, said he was “deeply moved” by the movie adaptation, which

became Japan’s third-biggest box-office hit of 2013.

Last year, Japan applied for the final letters of pilots written before their missions to be included as UNESCO Memories of the World.

“There is a

growing trend of glamorizing the kamikaze as the number of people who

experienced the war declines,” said Yukihiro Torikai, who teaches peace

and development at Tokai University. “Abe may be capitalizing on this.”

During

the war he flew a Mitsubishi A6M Zero, a fighter plane the National

Museum of the U.S. Air Force describes as the most famous symbol of

Japanese air power during World War II. The Zero was later customized

for kamikaze missions.

Morse Code “They would send Morse code messages to their base as they flew their sorties,” he said. “When the sound stopped, we knew the pilot’s life had ended and we placed our hands together.”

Tezuka kept his coming mission from his family to avoid upsetting them.

After

the war, he ran a business taking young Japanese workers at a soybean

oil company to the U.S. for training. He now spends his days ink-wash

painting and practicing calligraphy at his condominium overlooking

Yokohama, which is adorned with a model of a Zero fighter he received

from his daughter.

Iwai

spent much of his youth in Dalian, a Chinese city ceded to Japan from

Russia in 1905, after his father retired as a soldier. On returning to

Tokyo, he began to question the national regime that banned criticism --

or even discussion -- of the imperial system, and went on to study

philosophy at Keio University.

He

drifted between jobs after the war before learning Russian, which he

used at a trading company and later as a translator. Disaffected, he

sold all his wartime memorabilia and cut ties with his former comrades.

“When I first saw a human torpedo, I shuddered with the thought that this was going to be my coffin,” Iwai said. “It was a 15-meter-long iron stick. The cockpit was tiny and not fit for humans.”

A few months before the war ended, Iwai caught tuberculosis -- an illness that delayed his mission and may have saved his life.

Once

recovered, he was moved to a base near Tokyo to join the “crouching

dragon,” or fukuryu, unit of suicide divers in preparation for the

expected arrival of U.S. battleships. The frogmen had to wait underwater

to poke enemy vessels with a mine fitted to a bamboo pole.

After being transferred again, this time to Hiroshima, Iwai witnessed an event that changed everything.

“We were in a meeting on the morning of August 6, when there was a beautiful white flash in the sky, followed by a huge boom,” he said. “Hiroshima had been destroyed. A few days later, we learned it was the atomic bomb. And the war ended soon after.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Maiko Takahashi in Tokyo at mtakahashi61@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Andrew Davis at abdavis@bloomberg.net Andy Sharp, Rosalind Mathieson